By Gary Baum; Hollywood Reporter; Sept. 4, 2019

Long before the true-crime TV boom, a 1971 unsolved plane hijacking captivated America. Thomas J. Colbert’s journey to track down Cooper has now led to an elaborate theory of collusion involving the FBI and CIA.

For several days in May 2013, the Hollywood sting operation surveilled the grandfather at the condominium he shared with his third wife in the tony San Diego district of Bankers Hill. A $30,000-a-week private security group made up of former FBI agents, armed because of his violent past, watched his movements aboard the 45-foot cruiser Poverty Sucks, docked nearby. They tracked him at his boat repair shop, Coronado Precision Marine. And they followed him to his local P.O. box. When they felt confident that they’d clocked his routine, they sent in Colbert, the veteran newsman who’d hired them. He wore a wire and a hidden camera in his glasses.

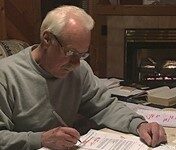

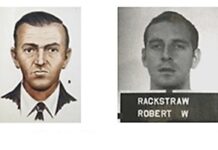

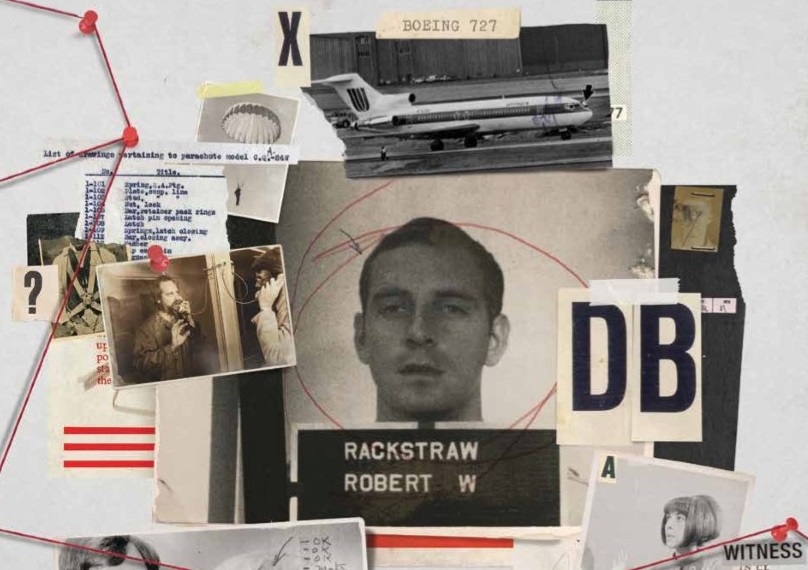

They’d opted for an ambush. Colbert had grown convinced that this old U.S. Army soldier with a distinctive criminal record, Robert W. Rackstraw, was in fact D.B. Cooper, who in 1971 skyjacked a Boeing 727 and then — with $200,000 in ransom money — parachuted from the plane into the Pacific Northwest night and enduring American myth.

At the boat shop, Colbert got straight to it, rolling out a chart the size of a table, which drew links between Rackstraw, his getaway partners and the ransom. “Why are you in the middle of this, Bob?” Colbert said, before switching gears to a sales pitch, offering a pair of $10,000 cashier’s checks made out in Rackstraw’s name if he’d sign over his story rights for a planned documentary and accompanying book. Colbert, a figure with a long history in Hollywood’s true-story business, explained that he already had enough material for his project to make it viable, but he’d much prefer Rackstraw’s participation. There’d be further paydays when the movie and book were released. The catch: “I wanted him to come clean,” says Colbert. “Several attorneys told me the most he was going to get was two to three years. I told him he might get time served and probation. He’d wear an ankle bracelet and then never have to buy a beer again.”

Rackstraw wouldn’t commit. So Colbert later emailed with a harder sell, advising that if he didn’t get on board, he and everyone who knows him would no doubt be hounded by the media that would follow. But if Rackstraw gave in, Colbert promised to “work to keep your neighborhood media-free and peaceful. Sign away and I’ll make it all happen.”

Instead, Rackstraw turned his attorney on Colbert. After 11 days , the cordial negotiations for his rights ended. This exchange would be the only direct contact between the symbiotic pair.

But their spiraling feud over Rackstraw’s alleged identity would persist for another six years. Only Rackstraw’s passing in July — of a heart condition, at 75 — would change their deadlocked calculus.

***

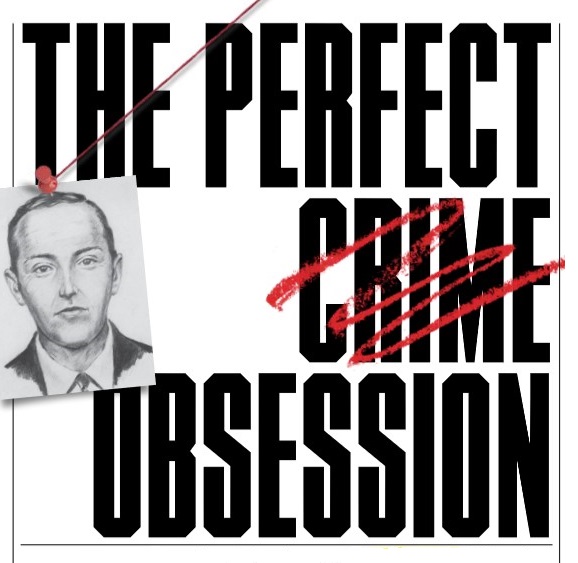

The ballad of Rackstraw and Colbert is a lesson in the lures and dangers of chasing the truth while also chasing a Hollywood deal. Decades before today’s true-crime boom and the neo-vigilantism of The Jinx and Serial, there was D.B. Cooper. The mystery — who was he and what happened to him? — has been a pop culture obsession ever since.

The skyjacking occurred Nov. 24, 1971. Once in the air, a man wearing dark sunglasses who’d purchased a ticket at Portland’s airport under the alias Dan Cooper — later misreported as D.B. Cooper — told a flight attendant he had a bomb. He demanded that the ransom money and four parachutes be delivered to him when the plane landed in Seattle.

The passengers were exchanged for the ransom. After refueling, Cooper signaled a course for Mexico at the minimum possible speed, opened the aft door and plunged into the wilderness. (The plane then landed safely in Reno.)

Nearly half a century on, Cooper remains a mystery. Only Amelia Earhart and Jimmy Hoffa rival his hold on the public imagination. And as with those others, a cottage industry of sleuths has arisen around the case. Call it the Coopersphere.

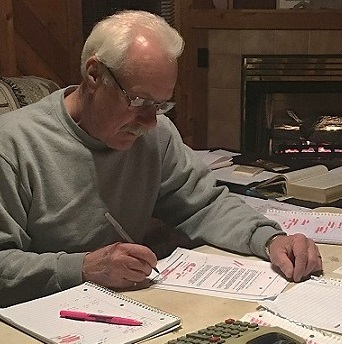

At its center now is 62-year-old Colbert, who claims to have spent six figures in his search to unmask the criminal, initially expecting he’d make his money back in a few years on book and movie deals. An affable, exuberant personality — Tom Arnold comes to mind — who now resides in Ventura County, Colbert is a colorful, old-school newsroom specimen. He worked at KCBS as a field producer and researcher, alongside then up-and-comers Paula Zahn, Ann Curry and Lester Holt.

Another colleague from that period, Connie Chung, emailed that she and Colbert “have kept in touch since.” And she is not surprised by his passion for this. “Tom dove into the D.B. Cooper mystery [with] the indefatigable curiosity to uncover the truth. He kept me posted on each layer peeled away. The story needs to be told.”

After a follow-up stint heading up research for a syndicated show at Paramount TV, Colbert started a service that provided clients (news programs, talent agencies, studios and publishers) with breaking leads on developable true-life tales.

“There are these people called story brokers,” CBS News President Susan Zirinsky once observed of such middlemen, when she was executive producer of 48 Hours. “I have found some dealings with some of the brokers to be grotesque.” Yet with Colbert, she emphasized at the time, “everything is above board.”

His news pipeline yielded dozens of discoveries, which were turned into big and small screen movies such as 1996’s Fly Away Home, 2001’s The Princess & Marine and 2012’s The Vow. He’d gotten the idea for the company after a news investigation he’d worked on, about a baby brokering ring, was turned into a 1994 movie on CBS starring Cybill Shepherd. (There was a Colbert stand-in with a mustache he still disproves of: “They made me look like Geraldo.”)

Chasing stranger-than-fiction tales of American life is deeply ingrained in his own life: He met his wife, Dawna, then a country-western singer, after she solved her mother’s murder by finding evidence that identified her father as the culprit. That story was dramatized by CBS in 1997 as Deep Family Secrets.

Colbert entered the Coopersphere in 2011, when a source tipped him off that some Cooper ransom cash discovered near an Oregon riverbank in 1980 was planted there in a scheme by the skyjacker to mislead authorities. Colbert pursued the lead to Rackstraw, at that point living in San Diego.

Rackstraw fit the established FBI profile as well as any Cooper contender. It wasn’t just that his old pictures looked like the sketch. While a soldier, he’d trained in aviation, demolition and parachuting, so he’d know how to make a bomb and jump out of a plane. He also had a potential motive, having at the time of the skyjacking only recently been kicked out of the Army for lying about medals, his rank and going to two colleges.

A 1971 FBI memo just released to Colbert by a federal judge appears to hint at things to come: “Extremely bitter” about his Army discharge, Rackstraw is then quoted in a letter to the brass: “I can only hope that I’ll never use the training and the education the Army gave me against the Army itself, as I would be a formidable advisary [sic].”

Rackstraw’s only sibling, Linda Loduca, heard about that “angry letter.” In an interview with Colbert, she revealed a local FBI man had brought it up in 1978 while looking at her fugitive brother (above) for bank fraud. Agent Warren Little believed “it was entirely possible, even plausible, this anger was at least part of the motive for the hijacking of Northwest Flight 305.”

Headquarters had tasked Little’s Stockton team to study Rackstraw during a series of run-ins with California authorities. In a memo to the director himself, they promised to “remain alert to any [Cooper] clues that might arise.”

At one point, the outlaw was charged with the murder of his stepfather — and acquitted. By 1979, while held on charges of check-kiting, possession of explosives and, of all things, theft of a small plane, he was asked in a TV interview about the rumor he was Cooper. “Could have been,” he wryly responded, “could have been.” This verbal footsie had been his M.O. ever since.

Rackstraw spent the next several decades living a quiet life, although Colbert claims his inquiry found that, privately, he would brag to multiple family members and friends that he was Cooper.

Colbert advanced his theory over several years, assembling a body of intriguing clues with the help of dozens of retired police, military vets, G-men, lawyers and others he’d cultivated during his media career and while teaching law enforcement training classes. Referring to them as his “Cold Case Team,” they lent their expertise on a volunteer basis. “I’d call them on their rowboats, at their golf courses, in their La-Z-Boys,” he says. “My pitch was, ‘I’ve found Cooper, I just need to nail him down.’”

In July 2016, three years after he ambushed Rackstraw, Colbert had amassed what he describes as 95 pieces of “physical, forensic, direct, testimonial, foundational, hearsay and documentary evidence.” He agreed to appear on a History Channel special about his team’s investigation called “D.B. Cooper: Case Closed?” which followed former FBI Assistant Director Tom Fuentes as he sorted through a number of suspects who’d gained traction over the decades.

But the head of the FBI’s Seattle Division announced on air that the FBI was done investigating — unless key physical evidence turned up. Meanwhile, the agent directly overseeing the Cooper case, Curtis Eng, explained that he’d reviewed the evidence independently amassed by Colbert and that “it didn’t prove that his suspect was Dan Cooper.” Late in the program, a flight attendant who’d dealt most directly with the skyjacker was shown old photos and video of Rackstraw. She said she didn’t recognize him as Cooper. (TJC: In regard to this paragraph’s conclusions, please read the very important FYI at article’s end.)

***

Colbert’s linked goals — proving that Rackstraw was Cooper and recouping his investment by selling his project about the pursuit — had been foiled by the History Channel fiasco. But this wasn’t something he was willing to accept. Colbert came to believe the FBI “bushwhacked” his team because they’d come close to proving that the bureau should’ve long ago brought a prosecutable case against Rackstraw. “I’m from the Reagan generation,” Colbert says. “I’ve always been a red, white and blue guy. I went in there hat-in-hand, and suddenly the FBI is messing with us. I was naive.”

Colbert and his national task force of sleuths — whose 1500 years of experience had been, Colbert felt, disrespected by the bureau — pursued multiple tracks. In 2017, a former cop led them to what was believed to be parts of the hijacker’s parachute in a remote area of eastern Washington State. His team turned the materials in to the bureau, along with the names of three of Cooper’s alleged getaway partners.

Then in 2018, after successfully suing the FBI to release much of its now-archived file, Cold Case Team member Rick Sherwood, a three-tour NSA veteran during Vietnam, decrypted code in six letters Cooper had sent to media outlets after the skyjacking, in which he’d apparently given away his identity.

According to Sherwood’s cryptography, the results and methodology of which Colbert has publicized, one decoded letter included the phrasing IF CATCH I AM CIA. Colbert contends he’s since established evidence that Rackstraw was a longtime CIA asset and now believes that collusion explains why the FBI stopped looking into him back in the 1970s as well as why, following the charade of keeping up an investigation for decades, it closed the case when his team grew too hot on its tail.

Colbert connected THR with multiple sources to back up his position. Retired Army LTC Ken Overturf was Rackstraw’s Vietnam commander in late 1969, when Rackstraw was a helicopter pilot for an intelligence unit in the Army’s 1st Cavalry Division. By Overturf’s account, Rackstraw’s demeanor along with security clearance issues ultimately led, by early 1970, to his exile to a less-sexy unit, flying maintenance support — “ash-and-trash missions.”

It was during these doldrums, at the Phuoc Vinh Base Camp near the border with Cambodia, that Rackstraw fell in with a man well known among the U.S. military there to be a CIA operative. Overturf and other tracked-down vets remember observing the grounded aviator accompanying the agent twice out of Phuoc Vinh in a stolen commander’s Jeep, loaded with explosives, and not returning for several days.

Two years later, forgotten government documents state Rackstraw was in neighboring Laos, flying for the spook-run airline Air America.

Colbert also offered up Jim Christy, a former high-ranking official in the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, who had a contact float the Rackstraw theory by a CIA source: “He said, ‘Listen very closely. I cannot confirm.’ Usually the answer is, ‘We cannot confirm or deny.’ It was code for ‘yes.’”

Colbert insists “I don’t do conspiracies.” Yet since the embarrassment of the History special, he attributes his run of bad luck in advancing his work to a hidden hand — a media “blackout” orchestrated by the FBI, in collusion with the CIA, attempting to shield Rackstraw. Like the plotline of the 2014 movie, Killing the Messenger.

By Colbert’s logic, all of this explains the mere lip service the network news editors and Hollywood gatekeepers have subsequently paid to his “historical” Cooper case developments for national audiences or a second documentary. Colbert cites his decades of experience fielding and vetting thousands of pitches in the news and movie trenches to contend that, while he’s used to hearing standard pass lines by editors (“Wrong demo,” “Too much breaking news,” “The boss isn’t into it”), this situation is different.

“With ten case update releases, we had no trouble interesting local, Canadian and international news editors. Close to a hundred stories went to ink or air around the globe. But not one national bite from USA networks, our papers of record or a wire story in the last two years? When the arrows all start pointing in the same direction,” he says, “my radar goes up.”

By February 2018, he’d grown so convinced that he held a press conference in front of the FBI’s headquarters with team members to announce that the bureau “has been covering up, stonewalling, and flat-out lying” about why Cooper-Rackstraw was cleared, in order to protect his decades of black-ops history with the CIA.

Michael London, Colbert’s manager and a veteran of the unscripted TV space beginning with Unsolved Mysteries in the 1980s, firmly backs him: “What I think is happening is that the production companies and channels that do these types of shows believe that in the future they’ll need the cooperation of the FBI and they don’t want to burn that bridge.”

To bolster his theory, Colbert shares a 15-page document, one of many he’d sent to THR over a period of months. The dense timeline tracks what he sees as an extensive suppression campaign, from the J. Edgar Hoover era through the current administration of director Christopher A. Wray, with what Colbert deems an incriminating, or at least disquieting, accumulation of correspondence.

***

There are no definitive answers inside the Coopersphere — only a disorienting fun house of mystery, doubt and bewilderment. Given the mania that surrounds its solving, today the crime can now feel quaint. After all, nobody died. But Cooper’s skyjacking long ago transcended an individual act to become an ever-expanding multiverse of tales — that most modern of Hollywood products.

Take that 2016 History doc, which caught the eye of a 30-something Alabama machinist who catfished (used a fake virtual identity to lure people online) in his spare time. He targeted Rackstraw on Facebook, posing as a 52-year-old nurse named Kelly Young. Then he contacted Colbert with the results of his inquiry: “I’m poor as dirt,” the man wrote Colbert of his obsession with the search for Cooper. “This is all I do and study sir. I have no hobbies any more, I’m addicted to the chase.”

Though his relationship with Colbert and his team proved short-lived because the machinist, in an apparent attempt to better lure his mark, escalated to racier messages, his catfishing did yield fresh intelligence from Rackstraw about his own Cooper-related musings. They include Rackstraw speaking with authority about the river cash (“I could be wrong, but I believe that’s all that will be found”), his own shadowy special-ops reputation (“Everything I did for our government raised questions”), his vexation with Colbert’s crew (“What I’m concerned with is those assholes beating me to a movie”) and his frustrated desire to finally take charge of his own life story by writing a film script about it. “I can’t get started until the bills are paid,” he typed to Kelly. “I’m already dead tired at the end of six-day work weeks. … I am looking for a place (office, apartment whatever) to gather all of my stuff and write.”

In mid-May, THR reached Rackstraw by phone. Rackstraw made it clear at the outset that he wouldn’t speak about his connection to the Cooper saga — unless, that is, he was paid on terms to his liking. “I’m probably one of the only people who can close the case,” he said. As for Hollywood interest in his story, he said that both WME and CAA had reached out, as well as other production companies whose names he couldn’t recall. (THR has confirmed they included Magical Elves.) But by his own account, his own hard bargaining had scared them all away.

Rackstraw was most fired up about Colbert, whom he regarded as a mix of irritant and hell-hound. While the four-time felon had said he’d think over speaking further, THR heard from him only once more, a short while later. He emailed a warning of Colbert’s “numerous attempts to dupe yet another media source.”

After Rackstraw’s death in July, THR talked with his attorney, Dennis Roberts, who said that Colbert’s investigation drove Rackstraw “nuts” and insisted “it’s all bullshit. He’s not D.B. Cooper.” In Roberts’ next breath, though, he said Rackstraw had been responsible for one of the many less-renowned copycat skyjackings that had followed Cooper’s — and this is why his client never sued Colbert for defamation. “It would have meant that [Rackstraw] would have to admit the second skyjack. He would have opened himself to a deposition.”

Roberts either wouldn’t or couldn’t provide the date of the other skyjacking, although he pinpointed it as between the date of the Cooper flight, Nov. 24, 1971, and that of another prominent suspect in the Coopersphere, Richard Floyd McCoy Jr., who was caught after bailing out of a Boeing 727 over Utah with $500,000 on April 7, 1972. Brendan I. Koerner, author of The Skies Belong to Us, a history of U.S. aircraft hijackings between 1961 and 1973, tells THR he doesn’t know of any other unsolved cases aside from the Cooper incident. “That sounds highly implausible,” he says.

Colbert, later digesting Roberts’ claim, is for once briefly at a loss for words: “I don’t know where to start. He’s carrying the water for a dead man.”

As for the business with the CIA, Roberts says he doesn’t know about it, except that Rackstraw did work in pre-revolution Iran as a pilot “teaching the Shah’s people how to fly helicopters.”

Maybe Rackstraw was a CIA asset. Maybe he was in fact D.B. Cooper. Or maybe he was an obsessive who enjoyed being taken for an American antihero. More than one of these things could be true. The only thing known for certain is that Colbert’s quest has remade the way he understands the world.

When he received word in July that Rackstraw had died, he turned into Paul Revere, alerting the press: “While my team absolutely believes he was Cooper, he was also a husband, father, grandfather and great grandfather. Our condolences to the family.”

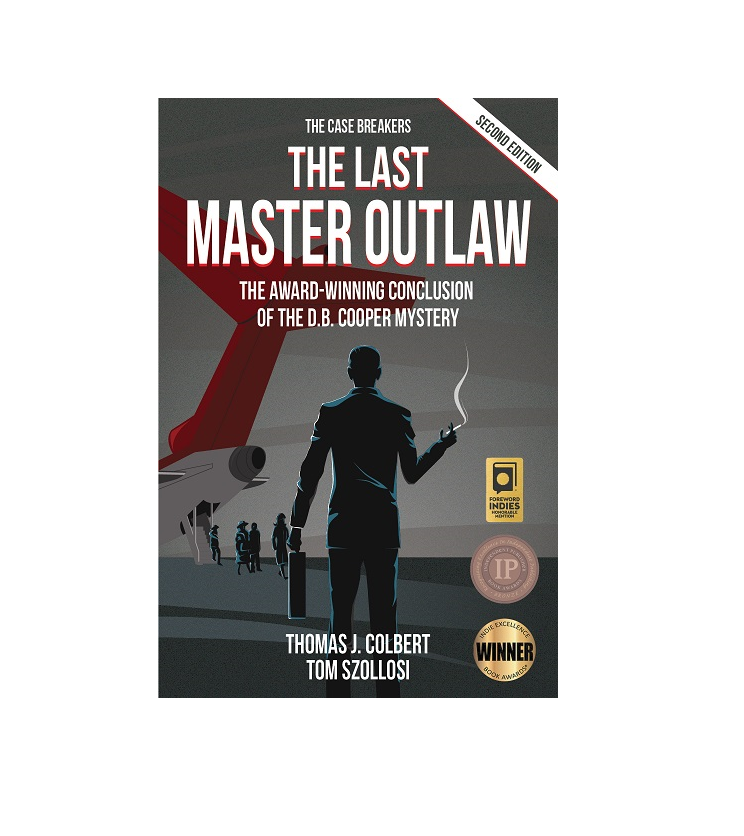

Media interest in his story spiked — “Fox News limo’d us in; Shep [Smith] did the interview” — including a spate of podcasters. And his acclaimed true-crime book, the self-published “The Last Master Outlaw,” received its 95th five-star review on Amazon.

The perfect criminal eluded the law. But order can still be enforced on the D.B Cooper narrative. As with so many mysteries, truth is consigned to play out as entertainment. The Making a Murderer documentarians, who like other darlings of the new age of true crime have seen their own facts and ethics called into question, investigated Steven Avery for a decade before their work first aired on Netflix. For Colbert, whose team spent seven years and counting in the Coopersphere, the journey continues. He still believes — and he’s still pitching.

##

FYI: Reporter Gary Baum did a fair job in reporting all sides of this very complicated quest. But when writing his conclusion paragraph about the 2016 History Channel show — its highest-rated special in two years — Baum didn’t include the shocking events that went down, three months earlier, during the production’s last shooting day (most of it cut from the program).

You’d now have to read chapter 20 of the team’s book to get those details — and that’s exactly what the FBI was counting on. So here they are in a nutshell:

After the cable network successfully negotiated for six months to get current Cooper case agents to “star” in its two-day program, 1) the team’s top 18 pieces of Rackstraw evidence and case arguments were secretly edited out of the show; 2) our five-year collaboration with the bureau was abruptly canceled; 3) all the gathered forensic materials — including crucial DNA and letter trails — were refused (FBI lied on TV; it never “reviewed the evidence”); and 4) the full hijacking file was quietly shipped off to D.C. and sealed.

For more on the FBI’s long cover-up of CIA maverick Rackstraw, see this link:

You’ll find the missing 18 pieces of evidence, bolded in court documents, at the “Case Evidence” menu on the top of the homepage. And PLEASE DO consider the investigative team’s book; its three national awards for true crime and astounding website testimonials should tell you exactly where the truth lies.

Happy hunting, TJC