INDIANAPOLIS STAR, Article #1; By Tim Evans; August 8, 2018;

Wheatfield, Ind. — It was the incongruous string of numbers in a December 11, 1971 letter that first attracted Rick Sherwood.

717171684*

“The numbers,” he explained, “just didn’t belong.”

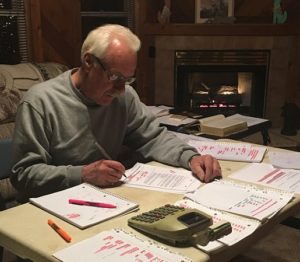

And he couldn’t let it go. So, for hours after hour last winter, Sherwood, 70, sat in his man cave trying to puzzle out a solution to one of America’s most enduring pop culture mysteries: Who was the brazen skyjacker that parachuted from a jet with $200,000 in 1971, the fabled outlaw known to the world as D.B. Cooper?

Sherwood believes he found the answer that has stumped the FBI for 47 years. He says it was encrypted in a 1971 letter and another allegedly written by the hijacker in 1972.

The Army veteran who worked with codes during the Vietnam War says he reckoned it out in his cedar-lined room surrounded by an antique Rock-Ola jukebox, a leather sofa and a row of windows looking out on the pastures, trees and cornfields behind his home about 20 miles south of Valparaiso.

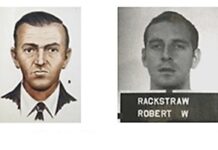

Now, he and Thomas J. Colbert, a producer and co-author of a 2016 book about the Cooper mystery called The Last Master Outlaw, are preparing to show how the code was cracked. Sherwood’s numeric calculations bolster Colbert’s book and his seven-year investigation, which identified the same former military pilot as the culprit: Robert W. Rackstraw Sr.

Rackstraw won’t say he did it, won’t say he didn’t

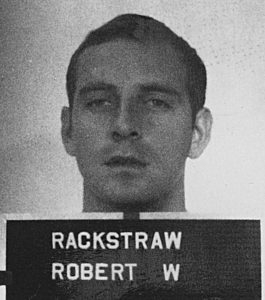

Newspaper accounts from the late 1970s reveal Rackstraw was among the potential suspects the FBI investigated, but the California man was apparently cleared.

He is the obvious person to debunk Sherwood’s finding. But in a seven-minute phone call with IndyStar, Rackstraw continued the cat-and-mouse game he’s played for decades. At times, it’s been clear to other interviewers that the veteran relished the attention and notoriety that comes with being associated with Cooper.

Rackstraw was a highly decorated Vietnam pilot with explosives and parachute training.

He left the Army in 1971, just months before the hijacking. In the years that followed his life included a series of ups and downs. He was accused, and acquitted, of killing his stepfather and later stole an airplane and faked a crash to escape an embezzlement trial. But he later earned a law degree and taught in the University of California system.

In the brief conversation with IndyStar, Rackstraw declined four direct requests to deny claims by Colbert and Sherwood that he is the hijacker known as Cooper.

“Don’t get down to the bottom line,” he groused shortly before hanging up, after being asked why he wouldn’t just say he isn’t Cooper. “That’s a 40-million-dollar question, for Christ’s sake!”

And Sherwood, who has no law enforcement training and had not used his knowledge of codes in fifty years, seems an unlikely person to have answered it.

And Sherwood, who has no law enforcement training and had not used his knowledge of codes in fifty years, seems an unlikely person to have answered it.

Whether he’s right or not remains to be seen.

The FBI, which identified and cleared more than 1,000 suspects, closed its investigation into America’s only unsolved hijacking in 2016 and is not likely to take another look at Rackstraw.

When announcing the case was closed, the bureau said it appreciated “the immense number of tips provided by members of the public,” but is now interested only in two pieces of evidence from citizen-sleuths attracted to the Cooper mystery: the parachutes used by Cooper or some of the ransom money.

Colbert claimed he was tipped to the alleged forest burial spot of those items. Exactly a year ago, a former senior FBI supervisor on his team turned in five dug-up materials, believed to be part of the parachute, to Seattle Division. Colbert said the surprised agents haven’t been heard from since.

An Army veteran from Indiana gets involved

Sherwood’s dive into the D.B. Cooper case started with a phone call out of the blue in 2015.

It came from Colbert. Sherwood was skeptical as he listened to the stranger who claimed to be a decades-long police trainer, writer and documentarian.

“He said, ‘Are you Rick Sherwood?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, who’s calling?’ He says, ‘My name’s Tom Colbert. I’m investigating the D. B. Cooper case and blah, blah, blah,'” Sherwood recalled. “And I’m going, ‘Oh yeah, right.’ In fact, it was true.”

Colbert had already zeroed in on Rackstraw as he was wrapping up work on his 2016 book. He enlisted Sherwood’s help while looking for Vietnam vets who may have encountered Rackstraw in the service. Sherwood was among more than a dozen men from Rackstraw’s unit that Colbert contacted to assist his “cold-case” team.

“He wanted somebody that was in the 371st and had dealt with Rackstraw,” Sherwood said.

Sherwood said he doesn’t believe he personally met pilot Rackstraw, but being in such close proximity, it’s likely they communicated by radio. Rackstraw filled in briefly as a helicopter aviator with the classified mission that Sherwood was assigned to from 1968 until 1970, when he concluded his 26-month tour of duty in Vietnam and returned to the states.

Sherwood said he doesn’t believe he personally met pilot Rackstraw, but being in such close proximity, it’s likely they communicated by radio. Rackstraw filled in briefly as a helicopter aviator with the classified mission that Sherwood was assigned to from 1968 until 1970, when he concluded his 26-month tour of duty in Vietnam and returned to the states.

Like many Americans, Sherwood was aware of the daring 1971 hijacking.

“I knew they gave him some parachutes, and he got a bunch of money,” Sherwood said. “That’s all I knew.”

But things changed after Sherwood took the call from Colbert.

Even though he hadn’t directly encountered Rackstraw, Sherwood and Colbert talked several times over the next few months. Those conversations led to Colbert mentioning Sherwood several times in his book, in passages describing the war-time conditions and the nature of his then-secret mission called Project Left Bank.

During his enlistment, Sherwood said he worked in radio communications with chopper pilots like Rackstraw, using encoded messages. The unit also attempted to capture and decipher encoded enemy messages.

Sherwood’s contact with Colbert piqued his interest in the Cooper case, so he read the sleuth’s award-winning tome, co-written by Tom Szollosi. But it would be another two years before Sherwood stumbled onto an internet article, featuring one of the letters the hijacker allegedly wrote after the crime.

There was something about its wording that perplexed Sherwood. And there was that nine-digit number and asterisk that didn’t seem to fit. He called Colbert and asked if he knew what the number in the December 11 letter meant. Colbert said he didn’t think anyone knew; even the FBI wrote in a memo it “remains unknown.”

Sherwood wondered if the number could somehow be the key to an old code. Suddenly, he found himself drawn even deeper into the enduring mystery that has spawned scores of books, movies and theories about the man behind the hijacking.

Sherwood goes ‘overboard’ trying to decode the letters

To family and others who know Sherwood well, it’s no surprise he would wind up neck-deep in the decades-old mystery. Sherwood admits he’s always ready for a challenge, even if it’s only the crossword puzzle in the Sunday newspaper.

“I just kind of go overboard doing things,” he said.

Stepping up to a challenge, in fact, has been a common theme in Sherwood’s life. As a young man, he enrolled in a difficult Army intelligence-training program on coding after a recruiter told him he didn’t have what it took to do the work. After the war, he reinvented himself when the job he expected to hold for a lifetime disappeared in the steel industry downturn. When he couldn’t find a U.S. flag after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, what did he do? He built a 30-by-20 flag out of scrap metal and 22,000 lights.

One thing he never expected, however, was a return to the coding work he’d done in the Army.

“To be absolutely honest with you, I never thought I’d ever have to use Morse code or any of the codes that I was trained on ever again,” Sherwood said, as he sat at one of two tables in the center of his man cave. He built the addition on the back of his home. It was supposed to be a deck, but morphed into a screened-in porch. And when his wife said she wanted windows? Well, Sherwood took up that challenge, too.

On the tables are neat stacks of papers and file folders. They include copies of the six post-hijacking letters written by a Cooper author. There also are dozens of pages of handwritten notes Sherwood has made, along with numeric calculations that hearken back to his days in the Army.

On the tables are neat stacks of papers and file folders. They include copies of the six post-hijacking letters written by a Cooper author. There also are dozens of pages of handwritten notes Sherwood has made, along with numeric calculations that hearken back to his days in the Army.

There is also a Playboy magazine. It’s from June 1970. The Playmate of the Year issue.

Sherwood said he spent long hours at the table last winter, going over what’s come to be known as “letter five.” After winning a half-year court fight to gain access to the FBI’s closed Cooper file through the Freedom of Information Act, Colbert was forwarded the typed note. It has a unique FBI “evidence” stamp dated Dec. 17, 1971.

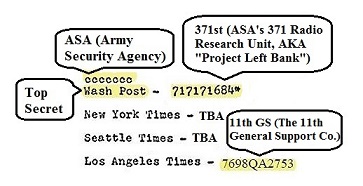

Old carbon copies of the letter were sent to the Washington Post, New York Times, Seattle Times and Los Angeles Times. The tone is taunting. “I knew from the start that I wouldn’t be caught,” it begins.

But there was no explanation for the string of numbers — 717171684*. As Sherwood pored over the letter, he also wondered why all the newspapers’ names had been written out, except for the “Wash Post.” And why had the writer marked the four copied sources with “ccccccc”?

Numbers and repeated words help crack the code

Aware of and hoping to confirm Colbert’s focus on Rackstraw, Sherwood set to work looking for a hidden message that would link the letter to him. Colbert said he, too, was anxiously awaiting the results of Sherwood’s sleuthing.

“I think it took me two weeks, just hour after hour,” Sherwood said. “I was going through everything I could possibly think of.”

Finally, he called Colbert back.

“I said ‘I need at least another set of numbers so I can correlate one to the other.'”

Colbert found a second set of scribbled numbers in an old folder that had apparently held the FBI-confiscated copy of the letter sent to the Los Angeles Times in 1971. He passed it to Sherwood, but it didn’t help.

Sherwood’s wife, Cheryl, recalled heading to bed alone many of those nights as her husband stayed at his table covered with papers.

“He would spend hours and hours and hours out there …,” she said. “I kept telling him, ‘You keep running this heater, you’re going to cost us a fortune.'”

Finally, Sherwood said, he gave up trying to use the two long strings of numbers to find some correlation to the alphabet. Instead, he focused on the first number itself from the Washington Post letter.

That’s when, Sherwood said, he had his first “a-ha” moment.

Could the three 71s in 717171 mean the 371st, the unit he and Rackstraw were both attached to briefly?

“When the 371st come up, I’m going ‘Yes, this is it. This is the beginning of breaking that code.'”

Using a simple letter-counting system, Sherwood said he unmasked other clues that pointed to Rackstraw. From the “ccccccc” he deciphered “Army Security Agency,” and from “Wash Post” he found “Top Secret.”

When he notified Colbert, the organizer was elated. He also had another challenge for Sherwood.

“You’re not done yet, Rick,” Sherwood recalled Colbert telling him. “I’ve got four other Cooper letters that have been out there all this time.”

A hidden message: ‘I’m LT Robert W. Rackstraw’

Colbert sent them all, and it didn’t take nearly as long for Sherwood to find what he believed were encryptions in each of them. He said all four letters included masked messages, using slight variations on the same code he’d used earlier.

The old Playboy magazine also helped. One of the Cooper notes was written with pasted alphabet letters cut out from a copy of that particular month. But there were just too many letters, Sherwood determined, to make sense of it.

A niece obtained the magazine copy from a friend’s old collection, and Sherwood saw the name of the centerfold. When he subtracted the letters from her name, he said, things started making more sense. Sherwood and Colbert said it appeared the hijacker was sending an encrypted message to accomplices who helped him escape after the hijacking.

Colbert claimed the team found two of those getaway partners still alive, and gave their contacts to the FBI. Again, not a word since.

It wasn’t until June that Sherwood said he located the mother lode — in a never-publicized sixth Cooper letter, also typed and court-released by the FBI. “I read it two or three times and got back on the phone and told Tom, ‘This is Rackstraw.’ I said, ‘This is his M.O. This is how he writes. He’s taunting. He’s doing everything like he’s done in these other letters.'”

Colbert’s response was direct: “Can you break the code?”

Sherwood went back to work on his tables in the man cave.

“A couple weeks later,” he said, “I had that one.”

“A couple weeks later,” he said, “I had that one.”

He had suspected the author had hidden his name in the final letter — and he believes he found it. Sherwood said he uncovered secret messages by keying in on oddly repeated words and phrases, then applying his decryption knowledge.

First, he focused on a line that says “and please tell the lackey cops, D.B. Cooper is not my real name.” Sherwood said the first six words hide the coded message “I’m LT Robert W. Rackstraw.”

Another line — “I want out of the system and saw a way through good ole Unk” — goes to the heart of the crime, Sherwood said. He contends the last four words translated to “by hijacking one jet plane.”

Sherwood admitted he could be wrong — finding what he wanted to because he was working from the assumption the letters were the work of Rackstraw. But he thinks there is just too much for it to be a coincidence or wishful thinking gone awry.

The code man explained it this way to the Oregonian, months ago: “What are the odds that the digits [in letter five] would add up to Rackstraw’s three exact Army units? A million to one. Astronomical. Rackstraw didn’t think anyone would be able to break it.”

Colbert, who is developing a new TV documentary to follow up the 2016 book, agrees.

The producer shared Sherwood’s findings with Rackstraw’s former Vietnam commander, Ken Overturf. The retired lieutenant-colonel, who has assisted Colbert’s cold-case team, found a copy of his 1950 cryptography manual. Through Pentagon records, he also determined Rackstraw “was the only soldier in the whole war” tied to those three units Sherwood claims to have found in coded letter five.

“We have doctrinal validation of the process that Rick Sherwood used to decipher all six of these messages,” Overturf said in a statement issued by Colbert. “In addition, DoD records show Rackstraw learned his coding method at Fort Bragg in a Special Warfare Operations Course in 1968.”

Robert Rackstraw: From war hero to murder suspect

Colbert’s book paints Rackstraw as disillusioned and vengeful after being forced from the Army for his documented misconduct. It also describes a man with the training, skills, moxie and motive to pull off the daring, first of its kind crime — and to survive a nighttime jump into a storm from the Boeing 727.

Colbert’s book paints Rackstraw as disillusioned and vengeful after being forced from the Army for his documented misconduct. It also describes a man with the training, skills, moxie and motive to pull off the daring, first of its kind crime — and to survive a nighttime jump into a storm from the Boeing 727.

Rackstraw had a history of minor scrapes with the law as a young man, but things got serious when he was accused of embezzling thousands of dollars in a check-kiting scam and hoarding explosives. Just before being charged, 40-year-old newspapers reveal Rackstraw fled the U.S. for Iran.

When the fugitive was returned in early 1978, Rackstraw faced a new charge: He was accused of killing his stepfather. Court documents and articles state that Rackstraw had hunkered down at this dead man’s remote mountain house during the first year after his alleged 1971 getaway.

Rackstraw was acquitted of the murder in the summer of 1978, but fled authorities again — the day before an October hearing in the embezzlement case. He rented a small airplane and claimed in a fake “May Day” radio transmission that he was crashing into Monterey Bay. Found under a false name with a repainted plane and phony tail number, he was taken back into custody in Southern California in January 1979.

During his earlier escape to Iran, two curious Stockton investigators first tipped the FBI to Rackstraw. Articles state a special agent and a state prosecutor both later asked him if he was Cooper, and in each interview, Colbert said Rackstraw “lawyered up.”

But a headline in the Reno Gazette on Feb. 9, 1979, said he offered a “tongue-in-cheek denial” to claims he was the daredevil during a jail interview.

“You want me to say I’m not D.B. Cooper — okay, I’m not D.B. Cooper,” Rackstraw told reporters for Gannett News Service. The story said “it is obvious that Robert Wesley Rackstraw delights in tantalizing reporters and authorities alike with another obscure hint in the 1971 skyjacking case.”

Robert Rackstraw calls D.B. Cooper sleuths ‘fake news’

In July 1979, Rackstraw was sentenced to two years in prison for four local charges. During a probation officer’s summary prior to the sentencing, the Stockton Record reported it “punctured (Rackstraw’s) self-made image as a war hero.”

While the veteran had received numerous medals and commendations, including a Silver Star for valor, a newspaper report revealed he “was not a Green Beret and that despite his claim of receiving five Purple Hearts, he actually had none and had never even been wounded in combat.”

Rackstraw was released from prison in 1980. His most serious criminal allegations behind him, according to Colbert’s book, Rackstraw went on to earn three diplomas, including a law degree. In the ensuing years, he taught arbitration at a state college and worked at a boat shop.

Despite his refusal to directly deny that he is Cooper, Rackstraw told IndyStar that Colbert’s claims are “fake news. It was a hurrah moment, I guess, a eureka moment for Colbert grasping at the last straws,” he said of the recent announcement that Sherwood had cracked the mystery of Cooper’s identity.

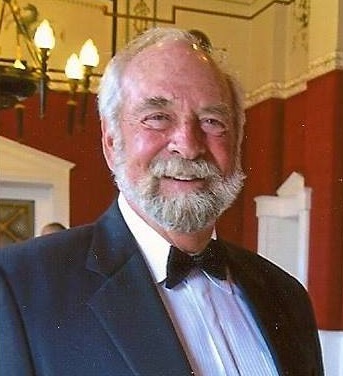

In a self-filed motion last year opposing Colbert’s request for the release of records from the FBI Cooper files, Rackstraw described himself as a “Disabled Homeless Vet.” But he listed a return address in Coronado, California, a tony resort town in San Diego Bay (Left: At 2014 party, one of his three black-tie events on Facebook).

In a self-filed motion last year opposing Colbert’s request for the release of records from the FBI Cooper files, Rackstraw described himself as a “Disabled Homeless Vet.” But he listed a return address in Coronado, California, a tony resort town in San Diego Bay (Left: At 2014 party, one of his three black-tie events on Facebook).

He also listed an email address that starts with “airbornebob.” Only Rackstraw knows if that moniker is a reference to his military days nearly five decades earlier, a nod to his role as a one-time Cooper suspect — or something else.

INDIANAPOLIS STAR, Article #2; By Tim Evans; August 08, 2018

Each letter is assigned an alpha-numeric value based on its order in the alphabet: A=1, B=2, C=3 and so on all the way through Z=26.

From there though, things get complicated. Like with the Navajo “code-talkers” of World War II, there are some gray areas in the interpretive code from Vietnam — requiring deep knowledge of Army-era slang, a specific suspect and a little faith.

Today, for the first time, Hoosier veteran Rick Sherwood reveals the method he used to uncover what he believes is the “smoking gun” that confirms the identity of the man behind the D.B. Cooper hijacking. Sherwood says he found the answer in coded messages in letters claiming to be written by the skyjacker and sent to newspapers after the 1971 crime.

Sherwood, working with Cooper-sleuth and author Tom Colbert, contends those messages identify the man behind the hijacking as Robert W. Rackstraw Sr., another ‘Nam vet living in the San Diego area.

Colbert is co-author of the award-winning book, The Last Master Outlaw, which makes the case that Rackstraw is the man who hijacked a flight from Portland to Seattle on Nov. 24, 1971. The brazen skyjacker then parachuted to an unknown fate with $200,000 in ransom money.

Rackstraw was investigated by the FBI and cleared in the years after the hijacking. In a brief interview with IndyStar, he declined to directly refute the claims he was Cooper, but also attacked the credibility of Colbert and Sherwood.

Whether they are right or not about Rackstraw remains to be seen. The FBI closed its Cooper investigation in 2016 and, according to Colbert, has shown no interest in his findings.

It was in an unexpected letter released from the FBI’s Cooper file earlier this year, and known as letter No. 6, that Sherwood reported finding the message: “I’m Lt. Robert W. Rackstraw.”

How decryption process works

So, how did Sherwood find and decipher the coded message? Here’s his explanation of the decryption process, which Colbert has copyrighted.

Sherwood said he started by returning to his military training and experience, which included working with codes during his 26 months in Vietnam. He began looking for hints that there might be messages in the letters. Things like numbers that didn’t seem to fit. And repeating words or phrases.

In December, Sherwood said he found what he believes were messages about Rackstraw’s military career in letter No. 5 by using a letter-counting system. In one example, he explained, the letters in “Wash Post,” the only newspaper name among four in the letter not fully spelled out, totaled 121. He believes that’s a reference to Rackstraw’s work on a project that was “Top Secret,” a term in which the letter values also total 121.

Sherwood said he made the connection by examining hundreds of words and terms relating to Rackstraw’s military service, looking for a numerical match that fit. The same process turned up three other ties to Rackstraw’s time in the service in the same letter: 11th G.S., his helicopter unit; ASA, for Army Security Agency; and, 317st for the radio research unit Sherwood worked in while Rackstraw briefly served as a pilot.

Noticed repetitive phrases

Sherwood is aware some may accuse him of backing into the “messages” because he was focused on Rackstraw, but he believes the odds of finding so many ties to Rackstraw make it more than coincidence or wishful thinking.

In the two-paragraph letter No. 6, Sherwood said he found four repeated words or phrases. They included “D.B. Cooper is not real” and “D.B. Cooper is not my real name.” He also found two references to “lackey cops.” The second examples of both were in the sentence set off by parentheses: “And please tell the lackey cops D.B. Cooper is now my real name.”

“If he’s saying D.B. Cooper is not my real name,” Sherwood explained, “I wondered if he might have hidden his real name in that sentence.” Using his letter-counting system, he found “and please tell the lackey cops” totaled 269. That was the same number he came up with for “I’m Lt. Robert W. Rackstraw.”

Rackstraw found two other repeated references in that letter. One was to “uncle” or “unk,” when the writer was referring to the government. The other was to “the system.” And again, in one instance they were combined in one sentence: “I want out of the system and saw a way through good ole Unk.”

When he examined the writer’s explanation of “through good ole Unk” he found the letter-count totaled 216 — a perfect match for “by hijacking one jet plane.”

Sherwood claims to have found similar cloaked messages in all six Cooper letters.

Colbert, a former CBS news researcher and police trainer who assembled a “cold case” team to help him tackle the Cooper mystery, said Sherwood’s decryptions add to his confidence that Rackstraw is the hijacker.

“Before the discovery of the coding, a judge, CSI professor and dogged defense attorney on our team had each declared our earlier evidence, including DNA, to be ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,'” Colbert said.

Now, with the addition of Sherwood’s findings, Colbert said his confidence level “is 110 percent.”

##