SEATTLE PI; By Senior Editor Daniel DeMay; June 29, 2018;

Rain fell hard through the dark November sky in 1971 as the Boeing 727 flew low and slow over southwest Washington State, “creating enough noise to shake a house,” said an FBI eyewitness.

The skeleton crew that remained on the Northwest Orient airliner huddled together in the pilot’s cabin, ordered there by a hijacker calling himself Dan Cooper who was alone in the otherwise vacant rear of the plane.

Dressed in a suit and acting as calm and easy as if he was on just another business trip, the man had used a bomb threat to take over the then Seattle-bound plan and shakedown the airline for $200,000 in ransom money. No one knew if the bomb in his briefcase was real, but they weren’t taking any chances, and the airline had paid the cash with little resistance. He’d also received the parachutes he requested.

Minutes later, the plane’s tail dipped enough that the pilot had to trim the aircraft to level it out. In all likelihood, that was when the hijacker who came to be known as D.B. Cooper jumped off of the extended bottom steps.

Forty-seven years later, the hijacker remains at large, and, despite a plethora of theories and suspects in the ensuing years, the only unsolved airborne robbery in the United States remains a mystery.

Or does it?

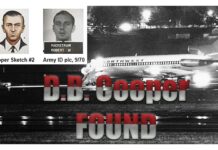

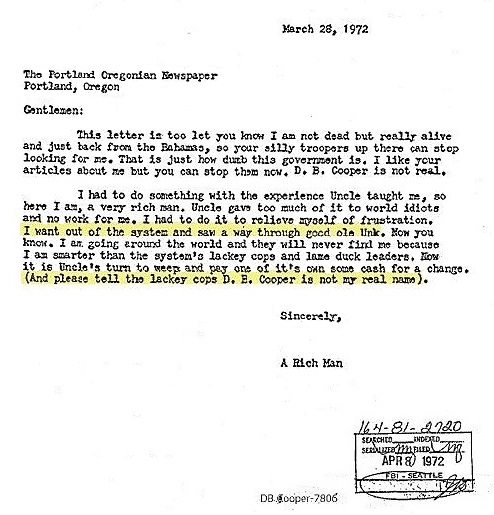

Yesterday, police trainer and true-crime producer Thomas J. Colbert revealed a taunting Cooper letter, typed months after the hijacking. It’s apparently the sixth note the FBI confiscated from a newspaper back in the day, and now released by a judge’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) order filed by Colbert. He suspects this one contains an Army-coded confession by the living daredevil.

Colbert and his partner-wife, Dawna, have spent seven years working with a 40-member cold case team, led by former FBI, to unravel the fantastic whodunit. But to them, the letter is only “icing on the cake.”

Colbert and his partner-wife, Dawna, have spent seven years working with a 40-member cold case team, led by former FBI, to unravel the fantastic whodunit. But to them, the letter is only “icing on the cake.”

It was the typed fifth letter, revealed by the Colberts in February and reportedly containing another code, pointing to specific military units, which closed the case for them.

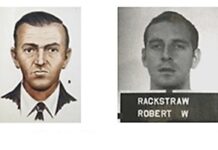

“According to his former lieutenant commander, he was the only man in the American Army with those particular three units, two of them top secret into the 1980s,” Thomas Colbert told SeattlePI. “So we know only (Robert W.) Rackstraw could’ve encrypted them in 1971.”

Rackstraw didn’t say anything when contacted by SeattlePI last November. But during a Courthouse News Service interview four months ago, the suspect, now 74, was pressed by a phone-calling reporter to either confirm or deny he was the fugitive. Rackstraw’s answer was unequivocal.

“There’s no denial whatsoever, my dear.”

Colbert’s narrative of how Rackstraw grew up and came to pull off the caper and escape — and everything else he was up to — would make a skeptic wonder. Most of it is detailed in Colbert and co-author Tom Szollosi’s award-winning book, “The Last Master Outlaw,” and the rest has made for fascinating reading the last two years. The facts known and confirmed were enough on their own.

An amazing story

The fugitive Cooper and two of the four parachutes were never seen again. The only evidence ever discovered was a small cache of $20 bills found along the Columbia River, nine years later in 1980.

The FBI officially stopped pursuing the case in 2016 but said it would review any physical evidence of the parachutes or the money that turned up.

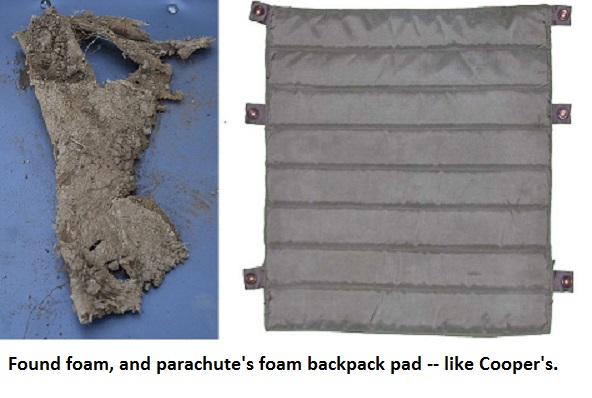

In August of 2017, a dozen of Colbert’s forensic experts, including a retired FBI supervisor, used a solid tip about where Cooper landed to track down bits of buried material they believed to be from the parachute. The group gave them and the remote burial site to the surprised Seattle Division agents. The next day, Colbert was emailed his one and only thank-you.

But the FBI has not visited the dig location or contacted the team since.

The forest tip, relayed by an old pilot, also told of three veteran accomplices using a truck and a small plane to pick up Cooper and help him escape. The four had plotted and practiced in advance, according to several farmer witnesses — which is all backed up by released FBI interview records.

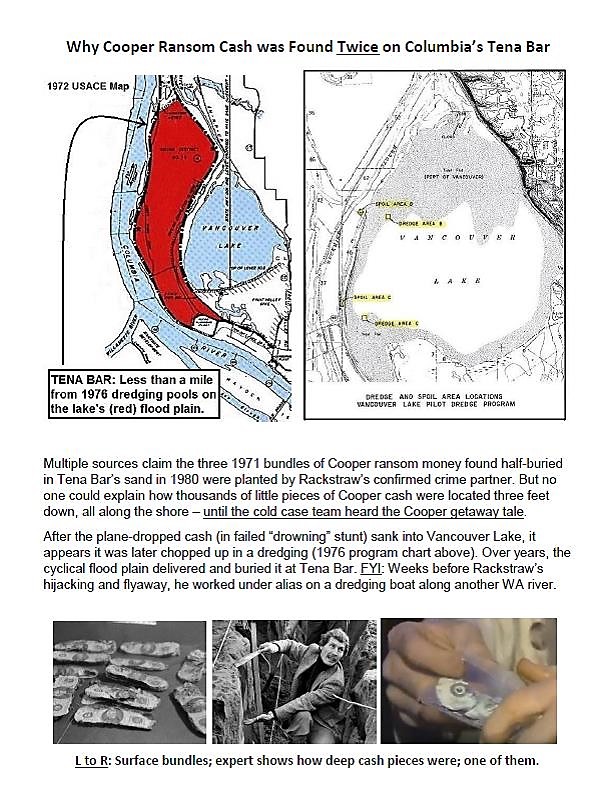

Another part of Colbert’s escape tale has Cooper tossing $50,000 of his ransom money into Vancouver Lake, as part of an elaborate scheme to suggest he drowned in the jump. But the cash didn’t wash up as planned, so a second effort planted Cooper money on the Columbia River shore where it was found in 1980. Which, no coincidence, just happens to be a short flood-plain away from that lake.

More of the amazing investigation’s twists and turns can be found at the team’s website, DBCooper.com.

FBI Cover-up?

Colbert said he found a dozen old Army warriors that served with Rackstraw in Vietnam. They confirmed he was involved in those secret military units unmasked in the fifth letter, and that he also freelanced on black ops missions for the CIA – a reason Colbert gives for him being let off the hook in the late 1970s.

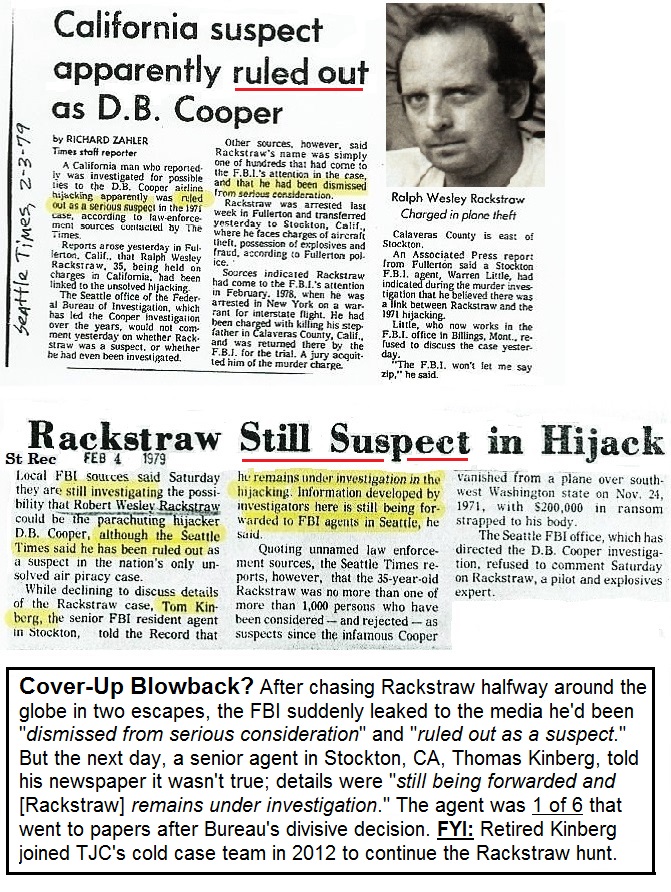

In that period, FOIA records and articles show the FBI helped local officials find him during two escapes, one as far away as Iran. Police also tipped the bureau to Rackstraw’s skill sets and similar Cooper looks. When nabbed, a special agent and county prosecutor separately asked Rackstraw if he was the hijacker, and each time he lawyered up. But after Seattle Division interviewed him in February of 1979, he was suddenly cleared.

Several FBI agents working on the case didn’t agree with that decision. When the brass quietly tipped the local Seattle Times he had been “ruled out,” other newspaper records show that six G-men immediately went to the media to say otherwise – three speaking on the record.

“That’s what made this incident so stunning,” said Colbert. “Six agents going public, each to a separate paper? This looks like the largest insurrection the FBI ever faced, but it never made the national news.”

Colbert also firmly believes current agents continue to work to hide old case details because of Rackstraw’s long ties to the CIA.

In 1971 inter-agency memos released by a court, current FBI have been allegedly redacting odd bits and pieces of old records, some standard and others more unusual. Several removed words appear to involve the mentioning of “D.B. Cooper letters,” or notes written and sent to newspapers by the alleged outlaw. Six of the “D.B. Cooper” references were recently whited out before the word “letter” in one particular memo — from the office of J. Edgar Hoover.

Colbert wondered, “Are they trying to protect the founder’s legacy, hide the truth, or both?”

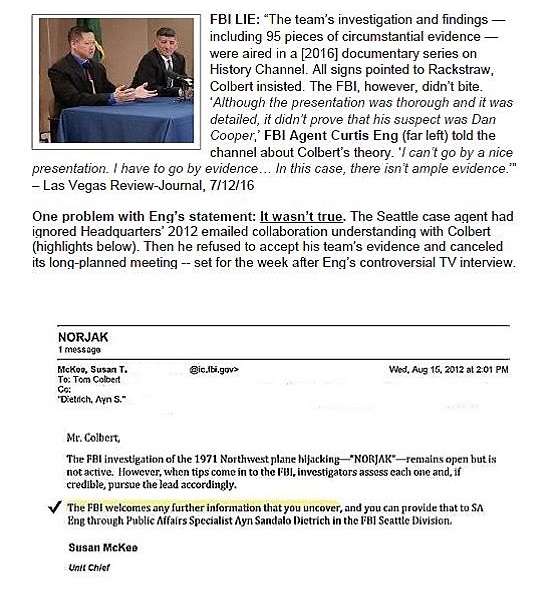

The team organizer said the FBI also misled the public when, in the 2016 History Channel documentary based around this hunt, Seattle case agent Curtis Eng told the audience he had reviewed Colberts’ evidence and declared there wasn’t enough to go on.

In reality, Colbert said Eng was only shown a few early samples of the 2012 circumstantial case. Colbert claims Eng also decided to ignore the typed collaboration email sent by FBI Headquarters that same year (above).

When it was time to meet the volunteer team and accept its almost 100 pieces of Cooper materials in 2016, Eng simply canceled the rendezvous. He and his Agent in Charge, Frank Montoya – who likewise told a post-show news conference audience that “there isn’t anything new out there” – then both quietly retired.

In all, Colbert said he has logged more than 60 incidents and court documents that reflect the FBI’s ongoing “stonewalling.”

One of his 13 retired agents, Behavioral Science Unit pioneer Jim Reese, added: “This door-slam was politics, pure and simple.”

Coded messages

The apparent encryptions in all of the Cooper letters, first spotted by a former Army code-breaker on the team, solidified the suspect for Colbert.

Vietnam veteran Rick Sherwood spent his career hunting hidden messages from the enemy; even now in retirement, eleven of the formulas are still in his head. When he saw the typed fifth Cooper letter, with odd letter and number combinations, he suspected it masked a secret communication, Colbert said.

After working it through for a couple of weeks, Sherwood found that it pointed to Rackstraw’s three Army units.

After working it through for a couple of weeks, Sherwood found that it pointed to Rackstraw’s three Army units.

And finally, this sixth letter mailed in March 1972, four months after the jump, had phrases and words that jumped right out at Sherwood. It also seemed a bit of a slap in the FBI’s face for failing to catch the author.

“I am not dead but really alive and just back from the Bahamas, so your silly troopers up there can stop looking for me,” the note, addressed to the Portland Oregonian newspaper, began.

But it was the odd phrases repeated in the letter (above) that got Sherwood excited.

“When Tom sent me the number six letter, I read it through several times,” Sherwood wrote in a statement. “I realized the typist repeated some of the words two or more times. There were two particular sentences that used the repeated words, two samples in each: 1) “D.B. Cooper is not real”; 2) “Uncle” or “Unk” (AKA Uncle Sam); 3) “the system”; and 4) “lackey cops.”

Using codes that would have also been known to Rackstraw, Sherwood decrypted the odd phrases, Colbert said.

The original sentence in the letter read: “And please tell the lackey cops D.B. Cooper is not my real name.” After unmasking the first half, it was a zinger: “I’m Lt. Robert W. Rackstraw, D.B. Cooper is not my real name.”

Similarly, the other secret found by the code man was utterly on the nose. The sentence, “I want out of the system and saw a way through good ole Unk,” was exposed to be, “I want out of the system and saw a way by hijacking one jet plane.”

To the skeptic, the messages may well be too much to swallow. But after team investigators reviewed the 1950 Army “Basic Cryptography” manual, Colbert said they became believers.

Hoover’s trying end

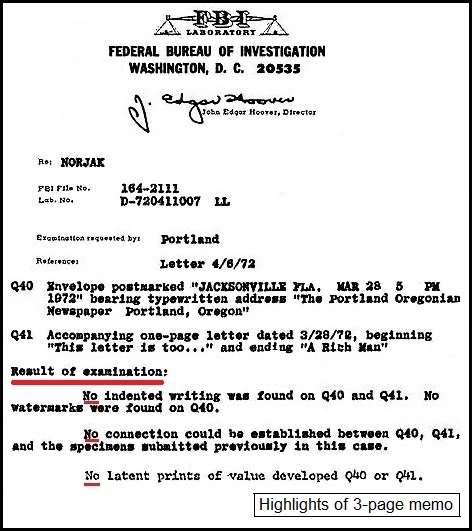

Colbert said the NORJAK case, as the hijacking was officially labeled, was a personal project of then-Founder J. Edgar Hoover. Memos show the 77-year-old “aging” director closely monitored field reports and supervised the laboratory work on all of the Cooper letters.

His technicians, however, reportedly couldn’t confirm the sixth one had a genuine connection to the previous notes, nor did it have any fingerprints or watermarks – like the others.

Hoover’s final lab report (above) in late April of 1972 detailed the lack of any useful evidence. Just four weeks after stamping his signature on it, the New York Times reported the founder was discovered on his bedroom floor, dead from high blood pressure and a heart attack.

“Hoover immersed himself in this frustrating hunt for his last five months,” Colbert said. “So it wouldn’t be a stretch to conclude the taunting Cooper had taken the life out of him.”