OREGONIAN; by Douglas Perry; January 3, 2018;

“Sirs, I knew from the start that I wouldn’t be caught,” the letter begins.

Postmarked Dec. 11, 1971, it was signed, “D.B. Cooper,” the name the press had given to the unknown criminal who, less than a month before the missive landed at several newspaper offices, had audaciously taken over Northwest Orient Flight 305 out of Portland. The skyjacker parachuted from the Boeing 727 with $200,000 in ransom – and disappeared. The mystery man quickly became a legend, the subject of folk songs, books and later a Hollywood movie.

Now more than 45 years after the crime, a task force of independent investigators, ironically led by former FBI agents, believes it has caught D.B. Cooper. That is, they believe they’ve identified who he really is — thanks to the taunting letter.

If only they could get the Bureau interested.

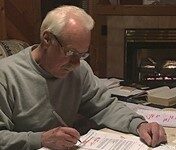

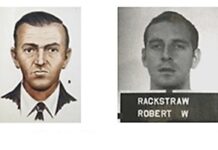

The 40-member team responsible for this major development concluded long ago that the famed skyjacker is former U.S. Army paratrooper Robert W. Rackstraw Sr., a decorated Vietnam War veteran and four-time felon who’s now 74 and living in the San Diego area. But the FBI, which investigated and cleared Rackstraw in the late ’70s, has taken little interest in the voluminous circumstantial evidence put forward by the group.

Documentary filmmaker Thomas J. Colbert, who set up the team, is convinced the Bureau refuses to pursue Rackstraw again because it would have to admit that a bunch of part-time, volunteer sleuths had cracked a case that it couldn’t.

“It’s not that they’re concerned about a circumstantial case,” Colbert says. “This is all about embarrassment and shame.”

The FBI, for its part, offers a different assessment. After considering hundreds of suspects over four decades, it decided to officially close the unsolved D.B. Cooper case in July 2016 “because there isn’t anything new out there,” Seattle Special Agent in Charge Frank Montoya, Jr., said at the time.

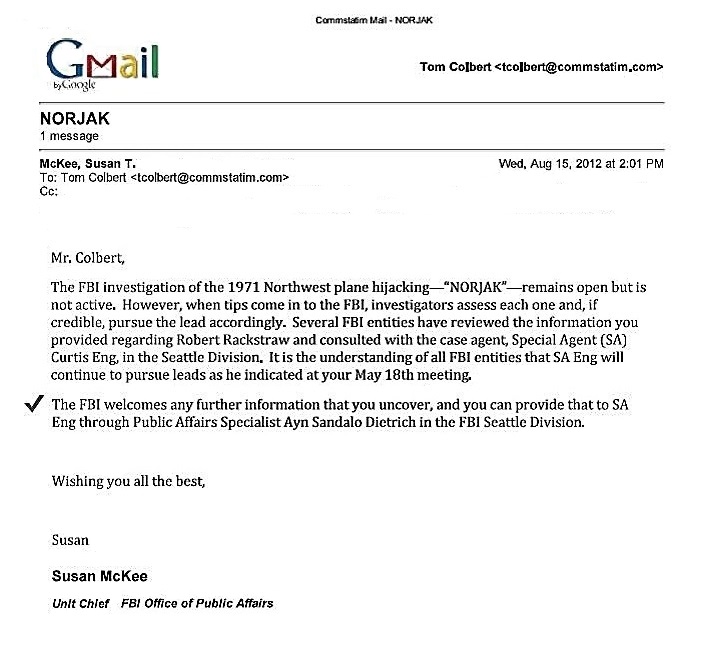

Colbert said Montoya’s surprise announcement instantly nullified an FBI Headquarters’ email (below) that promised the Bureau’s cooperation — something Colbert and his partner-wife, Dawna, have been relying on since 2012. It also left their team holding more than 100 pieces of evidence, including DNA, on the week they were scheduled to turn it all in.

“Never mind the five figures we’ve invested in polygraphs, forensic lab work, armed security and surveillance,” added the organizer.

Colberts’ original collaboration agreement with FBI Headquarters

Now eighteen months after the roadblock, there’s something new: Colbert believes a member of his team has broken a clever encrypted code from the skyjacker that was embedded in that Dec. 11 letter.

The Bureau still isn’t biting – it isn’t even responding to Colbert or his attorney anymore, or offering the press anything but public-relations boilerplate about being open to new hard evidence. So Colbert decided his team is “moving ahead without them.”

He and Dawna usually take two-to-three years to develop and market a crime story. But when the feds slammed the door on his volunteers, the Colberts made the decision to do “whatever it takes” to get to the truth. In the ensuing seven years, meanwhile, their two children have gone from grade school to college.

The portrait that’s emerged of Rackstraw is that of a conman and sociopath who is talented, charismatic, ruthless, violent – and has a lot of confirmed links to the Northwest Orient skyjacking.

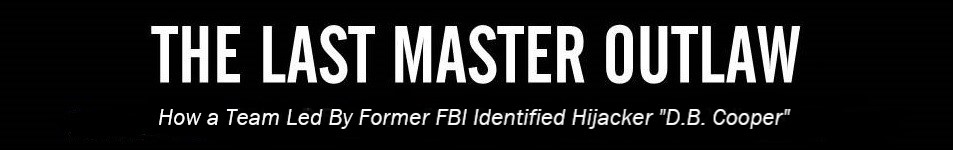

Colbert collected the team’s evidence into a 2016 book, “The Last Master Outlaw,” which has won three national awards for true crime. He’s co-produced a 2016 History Channel documentary on the investigation, “D.B. Cooper: Case Closed?” and is planning a sequel. And in between, the part-time police trainer has shared the lessons learned while blending old gumshoe methodologies with the latest law enforcement technology.

Now Colbert has come upon perhaps the most interesting — and most revealing — piece of evidence yet: the Dec. 11 letter, which the FBI released last November after a Freedom of Information Act suit by the team’s lawyer, Mark Zaid.

In the month following the skyjacking, a handful of envelopes from a “Cooper” author were sent to various newspapers (including The Oregonian). The FBI’s investigators downplayed the letters as hoaxes, but the typed Dec. 11 note — copied and sent to The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Seattle Times and Washington Post — was different.

Agents immediately seized all four. “They showed up at the (newspaper) offices and said, essentially, ‘Be a good citizen and hand them over,’” Colbert says. “And the newspapers did. It was a different time.”

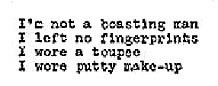

This letter, noted one FBI report from December 1971, “had the Bureau somewhat excited.” The reason: it offered up exclusive details in the Northwest Airlines case that weren’t ever released.

![]()

Witnesses on board the aircraft discreetly told agents the suspect appeared to be wearing “a toupee” and “putty makeup.” A forensic search of the airliner also revealed he “left no fingerprints” of value in the back of the plane.

The typing Cooper also wrote he had feelings of “hate, turmoil, hunger and more hate.” Colbert believes this was Rackstraw telegraphing his anger after being booted from his military career for lying and other transgressions, five months earlier.

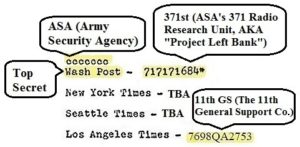

Then there are the seemingly random strings of numbers and alphabet letters at the bottom of the page. The Bureau’s investigators didn’t know what to make of them. In a Dec. 15, 1971, internal memo, the FBI laboratory wrote of one of the sequences: “The significance of the number ‘717171634*’, appearing next to copy count in the left corner, remains unknown.”

It remained unknown for 46 years — until a month ago.

Rick Sherwood, a relatively new member of Colbert’s team, has made sense of it and the other odd number/letter combinations in the note.

Sherwood served in the Army Security Agency (ASA), the military’s elite signals-intelligence outfit (like the NSA), during the Vietnam War. He describes the code training as “the equivalent of two years of college in 16 weeks. It was tough.”

Rackstraw briefly served as a chopper pilot in the ASA at the same time Sherwood was with the ground flight-control unit, though Sherwood said he didn’t know him.

After the FBI released the Dec. 11 letter, Sherwood began studying the possible cyphers in it, using his training to search for links to Rackstraw. It took him about two weeks to figure out the code and get his initial light-bulb moment.

Surfacing out of what appears to be a mishmash of unrelated numbers and letters were Rackstraw’s three Vietnam military units: the 371st Radio Research Unit and the 11th General Support Company, as well as the Army Security Agency. The two that were classified were even separated by a “Top Secret” rebuke.

Sherwood wasn’t surprised the FBI couldn’t crack it in the early 1970s “because it would have made no sense to them. For the agents to do it, they’d have to know a lot about the individual and our units.” (Rackstraw wasn’t identified as a “person of interest” until 1978, and his two secret programs remained that way until the late 1980s.)

Could Sherwood have accidentally created this solution to the code because he was trying to find a connection to Rackstraw?

“It’s not impossible,” the analyst says. “But what are the odds that these digits would add up to these three Rackstraw units? Astronomical. A million to one. Rackstraw didn’t think anyone would be able to break it.”

Sherwood walked The Oregonian through the methodical code-breaking process he used, with the understanding that the details wouldn’t be included in this article since they’re a key part of the second D.B. Cooper documentary Colbert is planning.

The show developer considers the Dec. 11 letter the cherry on the top of his years-long investigation, and he’s not alone. Western Illinois University criminal-science professor Jack Schafer, also a psychologist and former FBI agent, found Sherwood’s code-breaking work to be first-rate.

“Since these correlate with identifiers in Rackstraw’s (Army) life, I’m convinced this letter was written by D.B. Cooper,” he told Colbert in an email. “This is your strongest piece of evidence linking him to the hijacker.”

Lieutenant-Colonel Ken Overturf (ret.) was Rackstraw’s commander in his covert ASA chopper unit. He also reviewed Sherwood’s code-breaking, verified his methods in their old Army cryptography manual, then confirmed in Pentagon records that Rackstraw did indeed get this same training in 1968. Overturf’s take on all the developments:

“I’m confident that [Sherwood’s decryption work] can be validated via military historical intelligence research. I also do not believe that anyone else in the U.S. Army at that time could possibly fit the profile of these three units. The investigative path leads directly back to Rackstraw.”

Rackstraw himself, it should be mentioned, often has refused to rule out that he is the legendary skyjacker. He boasted back in the late 1970s that, given his skill set, he should be on the FBI’s list of suspects: “I wouldn’t discount myself, or a person like myself.”

When the TV reporter asked him point-blank if he was D.B. Cooper, he responded: “Coulda’ been. Coulda’ been. I can’t commit myself on something like that.”

All these years later he’s still playing the tease.

“They say that I’m him,” Rackstraw told a California reporter last fall. “If you want to believe it, believe it.”

Colbert is betting that viewers of his in-the-works documentary will believe it. Since the FBI doesn’t appear to have any interest in relaunching its D.B. Cooper investigation, he and his team are going to rely on the court of public opinion, rather than a court of law, to provide some sense of justice in the case.

His quarry, it turns out, apparently wants to do the same. As a result, Rackstraw’s and Colbert’s versions of events actually might end up aligning.

Rackstraw said last year that he was cooperating with film producers, who he refused to name but who it seems are only interested in his story if it includes him jumping out of a Northwest Orient commercial airliner in November 1971. Said Rackstraw: “They’re paying me to tell the story they want to hear.”

When asked how much Hollywood was forking over, Rackstraw claimed 40-million dollars. Remember, however, that the fanciful figure is coming from a convicted con artist.

NOTE: Over a year ago (10/16/16), “Bob” Rackstraw bluntly revealed his Tinseltown intentions to an anonymous “Facebook girlfriend” – who after their falling out, forwarded the unsolicited short exchange to the cold case team’s website, DBCooper.com.