COURTHOUSE NEWS SERVICE;

by Britain Eakin;

February 9, 2018;

WASHINGTON, D.C. – A group of private investigators says they have definitively identified the living daredevil who hijacked a commercial plane in 1971 and parachuted off with a $200,000 ransom, never to be seen again.

“Our criminal investigation is finished,” said Thomas J. Colbert, a police trainer and documentary producer who assembled the 40-member team led by retired FBI. “We have the man, we know who he is.”

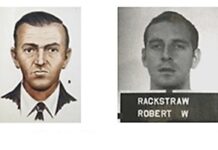

Standing with his attorney Mark Zaid and five of the team members on Feb. 1 outside of Bureau headquarters, Colbert said a former Army code-breaker has decrypted secret messages in several 1971 “D.B. Cooper” letters which confirm what the sleuths have believed for years: that fugitive is Robert W. Rackstraw Sr., a Special Forces-trained Vietnam pilot, explosives expert and former paratrooper living in San Diego.

Rackstraw’s name briefly came up in the FBI Cooper investigation in the 1970s, and the connection was spurred on in part by his oblique reply to a NBC News reporter’s on-camera query. “I’m afraid of heights,” the former paratrooper replied with a smile. “Could have been. Could have been. I can’t commit myself on something like that.”

Colbert included the clip in a 2016 History Channel documentary of his earlier findings. After the broadcast, the Washington Post quoted the author of “the most authoritative history of the Cooper investigation,” 2011 writer Geoffrey Gray, as saying Rackstraw was never treated as a serious suspect.

But Colbert countered, “Gray was uninformed. Old articles and security documents on Rackstraw led us to two retired agents that chased him halfway around the world during two fugitive runs, both back in 1978.”

Rackstraw has often denied that he is D.B. Cooper, but after Colbert’s Feb. 1 announcement he questioned why he should have to.

“There’s no denial whatsoever, my dear,” the 74-year-old Rackstraw said in a phone interview.

His longtime attorney, Dennis Roberts, did not return a voice message seeking comment. Both have threatened to sue Colbert and his team in the past, but no civil action has ever been filed.

Colbert credits that to his former team and his own book on their hunt, The Last Master Outlaw, co-authored by Tom Szollosi. “Thanks to its 50 pages of notes and three national awards for true crime, our conclusions are bullet-proof.”

Still, the FBI, which closed its investigation in 2016, has not announced plans to reopen the unsolved case.

Though the name D.B. Cooper has taken on folk-hero status, it stems from a miss-identification by the Associated Press in its initial reporting of the Nov. 24, 1971, hijacking of Northwest Orient Flight 305.

The Boeing 727 was taking off from Portland, Oregon, when a passenger who used the alias Dan Cooper passed a note to a flight attendant that demanded parachutes and $200,000, saying he had a bomb.

When the aircraft landed as scheduled in Seattle, Cooper traded the passengers for the ransom, then directed the pilots to fly to Mexico. The plane was flying at Cooper’s requested 10,000 feet when he opened its rear staircase and parachuted out somewhere over the Pacific Northwest with the cash.

CRACKING THE CODE

In the days following the crime, as the largest manhunt in U.S. history turned up few leads, several newspapers received five cryptic letters, all signed by a D.B. Cooper.

Rick Sherwood, a veteran code-breaker on Colbert’s team, said the first note sent on Nov. 27, 1971, used cut-and-pasted newspaper words and phrases. It stated “Attention!” and “Thanks for Hospitality,” followed by “Was In a Rut.” But the analyst also found two encryptions — one of them taunting the FBI.

According to Sherwood, the secret messages translated to “CAN FBI CATCH ME” and “SWS.” He said SWS stands for the Special Warfare School at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, where military records show Rackstraw learned to do coding with the Green Berets in 1968.

As a veteran of the Army Security Agency (ASA) – a sister program to the National Security Agency, specializing in military signals intelligence – Sherwood was familiar with the coding methods taught at Ft. Bragg. During the Vietnam War, he served in the ASA’s signal-tracking helicopter program called Project Left Bank. Rackstraw served briefly in the unit as one of the chopper pilots, but Sherwood said he did not know him personally.

The cold case team found Rackstraw’s initials, RWR, and a reference to CIA ties, in the coded message of the second D.B. Cooper note. This missive was sent in handwritten block letters on Nov. 30, 1971.

A CIA representative declined to comment on whether Rackstraw had ties to the agency. But Colbert asserted his team has now found credible witnesses to his mission departures with agency spies, plus 18 CIA assertions in courtroom records, police testimony, articles and statements from various credible eyewitnesses.

They all point to Rackstraw’s time during black ops in the 1970’s and 80’s, said Colbert. “Frankly, that’s why many of us believe the FBI didn’t charge him.”

Colbert’s team believes the D.B. Cooper letter-writer sent a third note on Dec. 1, 1971, to convey a discreet message to apparent accomplices. And in a fourth one mailed later that same day, the initials for another Rackstraw training unit, the National Guard Jump School, were found upon the decoding. The writer reverted back to cut-and-pasted lettering in both Dec. 1 notes.

The FBI kept a fifth Cooper letter, the only one stamped as “evidence,” under wraps for 46 years. Colbert and lawyer Zaid unearthed it a few months ago with a successful court challenge under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

In this type-written message, Sherwood said a random string of numbers and letters at the very bottom contained references to Rackstraw’s three Vietnam military units: the 11th General Support Company, the ASA, and the unit Sherwood briefly shared with Rackstraw, Project Left Bank.

Courthouse News went over Sherwood’s decoding methodology in a phone interview on the condition that it remain confidential, since it will form a key part of the next D.B. Cooper documentary Colbert is producing.

Sherwood noted that military ciphers are not made to be broken. In order to crack one, you need to know something about the individual who created it. Because of that, as he worked on deciphering any hidden letter messages, he had Rackstraw in mind.

Sherwood emphasized that the chances are very slim that he just saw something he wanted to see that pointed to Rackstraw. “If he in fact didn’t do it, then I wouldn’t have been able to match almost every word to his units. It added up because I knew every unit and I was in those units,” said Sherwood.

SKEPTICS & THE BUREAU

Amateur researchers on the hijacking case, fondly known as “Cooperites,” have proved almost as reluctant as the FBI to get on board with Colbert’s team.

“I do not believe that any of the letters signed ‘DB Cooper’ are from the skyjacker,” said Bruce Smith, a former investigative reporter who self-published a book on D.B. Cooper in 2015 – one of two dozen now available on the mystery.

Colbert and several of his former FBI investigators, however, maintain the fifth Cooper letter contains details that only the daredevil and the Bureau knew. For example, it states the jumper left no fingerprints behind and that he wore a toupee and putty make-up.

According to memos released in the FOIA order, senior agents determined those claims to be true through witnesses and a forensic search of the airliner. Colbert said he has follow-up documents showing those facts were quickly integrated into the investigative record.

Though Smith waved off Colbert’s findings as “quirky circumstantial evidence,” he admitted the material might inch Cooperites closer to the truth.

Attorney Zaid also has a theory about why the FBI failed to act on more than 100 pieces of additional evidence they provided, including DNA and fabric samples from a dig site where they believe they found pieces of Cooper’s parachute.

“I do think now, having identified this individual, that the FBI is frankly embarrassed that they let him slip through their grasp back in the late ’70s,” attorney Zaid said during the Feb. 1 press conference.

The FBI put the D.B. Cooper investigation on the back-burner, but public information officer Ayn Dietrich-Williams with the FBI’s Seattle Field Office said any physical items sent the Bureau are reviewed and given an appropriate follow-up. She noted, however, that the FBI does not necessarily provide updates to tipsters.

Even, apparently, when they are former special agents.

FYI: For more on the letters and code-breaking, see the media releases at the top of Latest News under “The Smoking Gun on D.B. Cooper” heading.

What was Rackstraw’s home town? What happened to his Wife? Did Rackstraw have children, what happened to them? Why was the pilot so reluctant to give information? How is it possible that a suspect when given an answer of “I am not willing to commit to to anything like that,” instead of simply saying NO I was not involved is not further questioned?